Stax Number Ones

“Jody’s Got Your Girl and Gone” by Johnnie Taylor

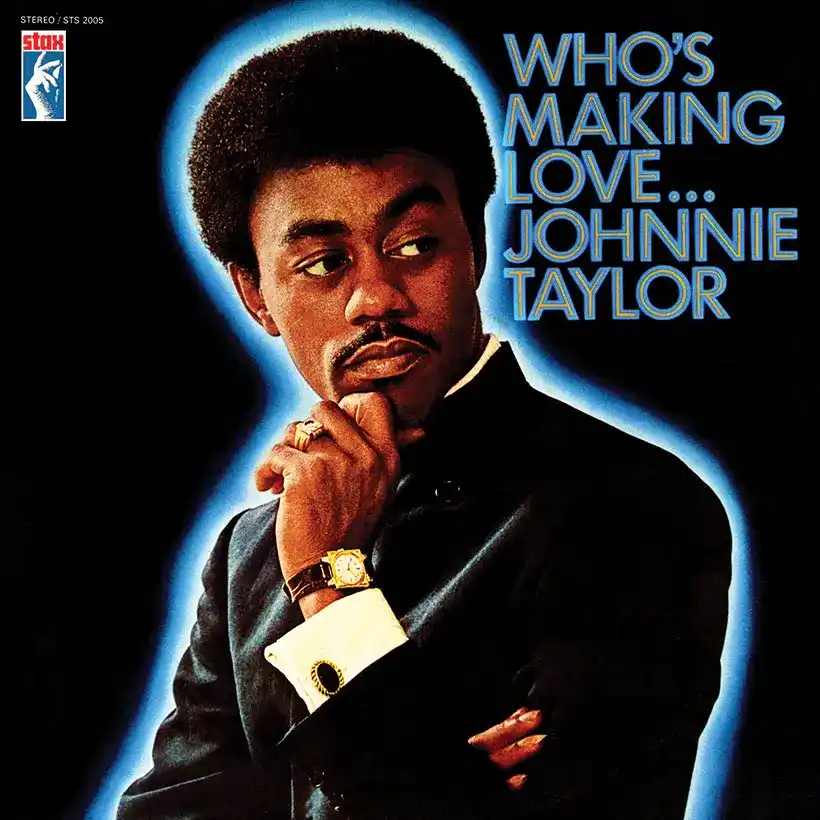

Dubbed affectionately the “Philosopher of Soul,” Johnnie Taylor turned his swagger and streetwise edge into a knack for converting taboo topics into Gold records. Although he honed his vocal chops in gospel quartets as a young man, his crossover into soul stardom took shape through a series of cautionary tales that became chart-toppers. Between 1968 and 1971, Taylor landed two explosive No.1s on the R&B chart that doubled as moral sermons for the romantically betrayed: “Who’s Making Love” and “Jody’s Got Your Girl and Gone.” On paper, both tracks dealt with infidelity and insecurity. On wax, they marked Taylor’s transformation into one of soul music’s sharpest narrators—and two defining moments for Stax Records during a critical period of reinvention.

Dubbed affectionately the “Philosopher of Soul,” Johnnie Taylor turned his swagger and streetwise edge into a knack for converting taboo topics into Gold records. Although he honed his vocal chops in gospel quartets as a young man, his crossover into soul stardom took shape through a series of cautionary tales that became chart-toppers. Between 1968 and 1971, Taylor landed two explosive No.1s on the R&B chart that doubled as moral sermons for the romantically betrayed: “Who’s Making Love” and “Jody’s Got Your Girl and Gone.” On paper, both tracks dealt with infidelity and insecurity. On wax, they marked Taylor’s transformation into one of soul music’s sharpest narrators—and two defining moments for Stax Records during a critical period of reinvention.

Born in Crawfordsville, Arkansas, in 1934 and raised by his grandmother in West Memphis, Taylor came up musically in the gospel world. He sang lead for the Highway Q.C.’s and eventually replaced Sam Cooke in the Soul Stirrers. His switch to secular music came at Cooke’s urging, who signed him to his SAR label in 1963. But after Cooke’s death the following year and SAR’s subsequent collapse, Taylor found himself without a label or a clear path forward.

That changed in 1966, when Stax’s Al Bell brought Taylor into the Memphis fold, drawn to his commanding voice and raw charisma. His early output showcased his ability to merge his gospel sensibilities with a down-home, bluesy attitude. But it wasn’t until late 1968 that he landed his breakthrough: a song resurrected from a demo that seemed unlikely to find a home after several producers had previously passed.

“Who’s Making Love” came from the trio of Bettye Crutcher, Homer Banks, and Raymond Jackson—a songwriting team dubbed “We Three.” Inspired by a line lifted from a Frank Sinatra TV special, the track reworked a 1920s novelty into a funky, finger-pointing anthem. Its premise was simple but clever: While men run the streets, women might do the same. Taylor brought it to life with the fervor of a fiery sermon and the helter-skelter panic of a philanderer. The topic would soon prove to be a lightning rod.

The record was finished under the direction of Don Davis, a Detroit-born guitarist-turned-producer who had begun working with Stax at Bell’s invitation. Davis took the rhythm track—cut in Memphis—and added layers of polish back in Detroit, applying vocal touches and overdubs that broadened the song’s appeal. Released in the fall of 1968, “Who’s Making Love” climbed to No.1 on the R&B charts and peaked at No.5 on the Billboard Hot 100, giving both Taylor and Stax their most significant commercial success to date.

But the song’s impact stretched beyond chart success, helping define Taylor’s artistic identity as a performer who balanced smooth charisma with a knowing wink at men’s worst instincts. At a time when Stax was still grappling with the loss of Otis Redding and the end of its partnership with Atlantic Records, the hit offered both a crucial lifeline and a potential sign that victories could lie ahead in the label’s next era.

In the years that followed, Taylor and Davis forged a sometimes uneasy but successful partnership. Davis, an outsider influenced by Motown’s prolific output, often faced pushback from Taylor, as the producer encouraged to follow up “Who’s Making Love” with a similarly styled hit. Once they found harmony together, they made good on that promise with “Jody’s Got Your Girl and Gone.”

Where “Who’s Making Love” called out hypocritical men in the abstract, “Jody” aimed a more vivid threat: a smooth-talking interloper who could be anyone—or everyone. The track began life as an instrumental Davis had shelved for months—until a friend dropped a line in casual conversation: “Jody’s got your girl and gone.” The phrase struck Davis instantly. A full lyric took shape that night, and with further contributions from songwriter Kay Barker and vocal backing from the Dramatics, the track was primed for Taylor’s delivery.

Released in December 1970, “Jody’s Got Your Girl and Gone” rose to No.1 on the R&B chart, displacing Rufus Thomas’ “(Do the) Push and Pull,” and cracked the Top 30 on the pop charts—proof that the archetype of Jody, the girlfriend-stealing figure lurking in soul folklore, resonated deeply.

Between the two hit songs, Taylor built a confessional and confrontational persona by making a daring approach to bring melody to topics often whispered about in private. These aren’t just songs; they live on as snapshots of shifting gender dynamics, romantic paranoia, and street-level wisdom, delivered with a style as unique as the performer who supplied them.

by Jared Boyd

Stax Number Ones ARCHIVE

Mr. Big Stuff

“(Do The) Push and Pull (Part 1)” by Rufus Thomas

“Jody’s Got Your Girl and Gone” by Johnnie Taylor

“(Sittin’ On) The Dock Of The Bay” by Otis Redding

“Knock On Wood” by Eddie Floyd

“Hold On, I’m Comin'” / “Soul Man” by Sam & Dave