Stax Songwriter Series

The Mad Lads

The Mad Lads

Widely known as a bastion of soul music cultivated by the groove and culture of the Southern United States, the Stax Record Company, in actuality, produced a large number of soul acts whose stylings appealed to the sensibilities of soul fans in other regions of the country. Notably among those acts are the Mad Lads, a group comprised of high school students reared mere blocks away from the Stax headquarters.

While the group of young men formed their harmonic partnership within the South Memphis shadow cast by the legendary Stax studio and record label, the Mad Lads leaned heavily into the doo-wop-infused sweet soul commonplace in cities such as Philadelphia, Detroit, D.C., and Chicago in their heyday. And today, the group is widely revered by collectors of so-called “lowrider music,” popular among car clubs in Southern California.

Though they eventually underwent personnel changes, the core group began with Booker T. Washington students Julius Green, John Gary Williams, Harold Thomas, and William C. Brown, III.

Brown, who would go on to serve as a pivotal and valued engineer during Stax’s later period, made acquaintances with the company’s owners, Jim Stewart and Estelle Axton, just as the business was opening its doors. Soon, Axton would give the eager young musician work as a clerk in the adjacent Satellite Record Shop. The teenager would also lend backing vocals to early sessions recorded in the studio.

The quartet that would eventually leave an impression on Stax and soul music history began with the four schoolmates, most of whom had participated previously in local talent organizations such as WDIA’s Teen Town Singers, performing under the name the Emeralds. When Brown brought his friends to meet Stewart and Axton, several months of courting netted the young men an opportunity to record dance record “The Sidewalk Surf.” In Harold Thomas’ absence, singer Robert Phillips stepped up to complete the recording. Upon discovering that the Emeralds’ moniker was already in use by another group, label performer, songwriter, and public relations head Deanie Parker adorned the rambunctious teenagers with the name the Mad Lads. The name was a backdoor nod to Reuben “Mad Lad” Washington, a local disc jockey with a penchant for playing records from the label, as well as an on-the-nose reference to the zany temperament of the quartet’s members.

Following “Sidewalk Surf” and “Surf Jerk,” the Mad Lads’ kitschy and nostalgic debut entry into the singles market, in 1964, the group would eventually get the chance to helm their own writing efforts. William C. Brown landed work with his pen first, serving as a co-writer alongside Isaac Hayes and J. R. Bailey, on “Tear-Maker,” the B-side to the Mad Lads’ 1965 hit, their first release under the Volt imprint, “Don’t Have to Shop Around.”

The larger group would score writing credits on four sides in 1966 featuring songs written by all four then-members: Green, Brown, Phillips, and Williams. These include the songs “Come Closer to Me” and “You Mean so Much to Me,” which were released as B-sides and appeared on the group’s debut LP, In Action, that same year. The remaining two songs appear together as “I Want a Girl” backed with “What Will Love Tend to Make You Do.”

Member Julius Green found success away from the group, contributing a co-writing placement to Otis Redding’s “Good to Me,” a single found on the back side of Redding’s “Fa-Fa-Fa-Fa-Fa (Sad Song)” and his The Soul Album LP, both released in 1966.

That year, fate would alter the Mad Lads’ upward trajectory, when Williams and Brown were drafted to join the military. Alternate members, Quincy Billops, Jr., and Sam Nelson, joined to fill the hole in the group’s lineup. Billops presented additional services as a co-writer on both sides of the group’s 1967 single “I Don’t Want to Lose Your Love” and “These Simple Reasons,” as well. Phillips, Green, and Williams share co-writing credit on the single, too.

However, the absence of two core members put a strain on the group’s productivity. Upon Williams and Browns’ return from duty in 1968, the decision to reinstate Williams’ membership proved to be a reluctant one, with other members initially intending to go on without him.

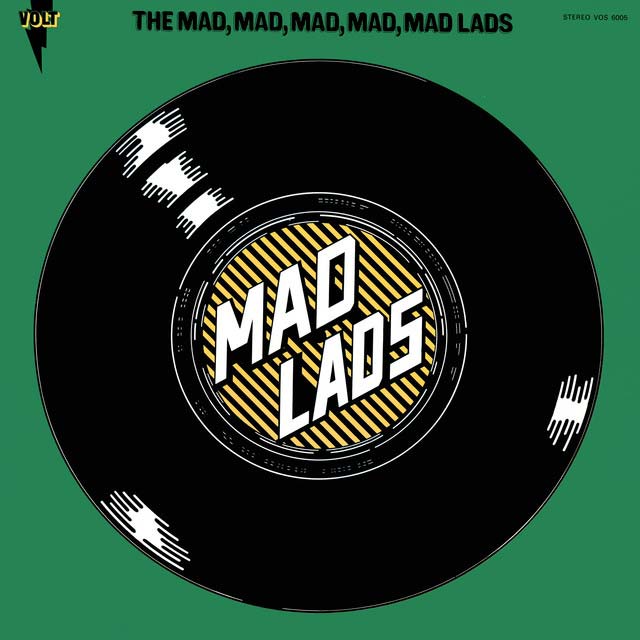

1969 album The Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad Lads

The rejuvenated Mad Lads enjoyed moderate success. Their 1968 single “So Nice” ranked at no. 35 on the U.S. R&B chart, bringing along with it a B-side co-written by John Gary Williams titled “Make Room.”

Williams’ ability as a songwriter shone bright over the group’s next two albums. The Mad Lads’ 1969 album The Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad Lads features two songs co-written by Williams and Booker T. Jones: “It’s Loving Time” and “Make This Young Lady Mine.” And, after the Mad Lads entered yet another brief hiatus, Williams returned with the group in 1973 to release A New Beginning. On that album, he serves up co-writing efforts, “Pass the Word (Love’s the Word)” and “I’m so Glad I Fell in Love With You.”

Between the two albums, in 1972, Stax labelmates the Soul Children, recorded “All That Shines Ain’t Gold,” written by John Gary Williams and Tommy Tate.

Naturally, when Stax released Williams’ solo LP the following year, Williams did the heavy lifting with writing, emerging with the funky opener “I See Hope,” and the introspective closer “The Whole Damn World Is Going Crazy,” among other original tunes.

Simultaneously, William C. Brown began an impressive climb up the ladder of Stax’s high-profile staffers. He worked frequently as an engineer, for which he is credited on such seminal releases as Isaac Hayes’ Shaft and Black Moses, Frederick Knight’s I’ve Been Lonely for so Long, and David Porter’s Victim of the Joke?….An Opera. He also began the 1970s with a burst of writing credits, including the Temprees’ “My Baby Love,” the Bar-Kays’ “Son of Shaft,” and the Mad Lads’ “I’m so Glad I Fell in Love With You,” all in 1971.

Together, Williams and Brown would connect to bolster Stax’s growing impressions in gospel by pairing the Rance Allen Group with their composition “Heaven Is Where the Heart Is,” in 1973.

The Mad Lads would continue to perform and release the occasional album under various lineups after Stax’s then-closing, in 1975. In 1990, the group got together for a reunion LP called Madder Than Ever on a revamped Volt Records.

– Jared Boyd

The Songwriters Series ARCHIVE

Frederick Knight

Rance Allen

The Mad Lads

Carl Hampton and Homer Banks

Eddie Floyd and Al Bell

William Bell and Booker T. Jones

Eddie Marion, James Banks, and Henderson Thigpen

We Three (Bettye Crutcher, Raymond Jackson & Homer Banks)

Eddie Floyd and Steve Cropper

Booker T & the M.G.’s

Steve Cropper and Otis Redding