Stax Songwriter Series

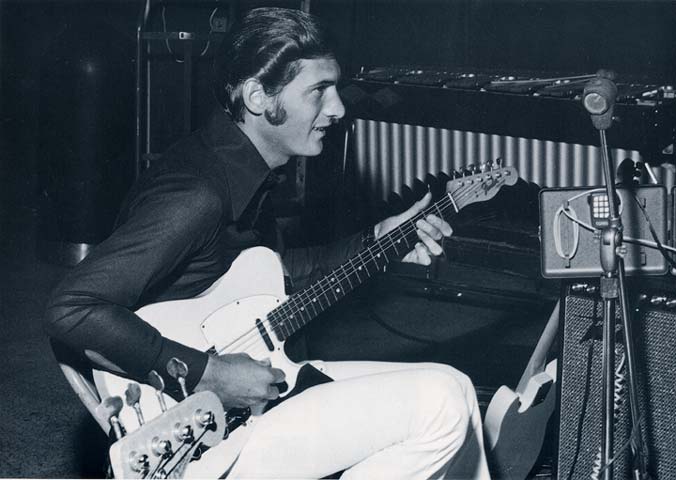

Steve Cropper

In the universe of soul music, individual stars can shine brilliantly from a distance, but find new definition to their luster once they magically align. At Stax Records, such an encounter happened often. In the case of the chance meeting between Steve Cropper and Otis Redding, a “big bang” occurred that would produce a slew of hits, in turn influencing at the time of delivery that the sound of Memphis while expressing a far-reaching impact around the globe.

Born in 1941 on a farm in an unincorporated town in southwest Missouri, Steve Cropper’s family relocated to Memphis, Tennessee, when he was nine years old. Captivated by the guitar at a young age, he took up odd jobs as a teenager to save up money and order his first instrument from a mail-order company. Unable to afford instruction, Cropper would rely on neighborhood friend Charlie Freeman to relay everything he learned after he returned home from private lessons with his guitar teacher.

Cropper would find his first songwriting success with the help of another boyhood friend, B.B. Cunningham, who aided the 16-year-old in securing a small tape recorder to document a scratch riff that would eventually be recorded by Sun Studios standout Bill Justis. Their collaboration, “Flea Circus,” would be released as a single in 1959.

Pairing again with Freeman, Cropper would find a band, The Royal Spades, enlisting the help of other schoolmates with an insatiable taste for the rhythm and blues that spilled from Black nightclubs in and around Memphis. They’d find allies in the likes of bassist Donald “Duck” Dunn and saxophonist Charles “Packy” Axton, the latter whose knack for music was less an asset to the group than one very alluring intangible: His mother Estelle Axton co-owned Satellite Records and its studio. It would soon become the Spades’ proving grounds, much to the chagrin of Estelle Axton’s brother and business partner, Jim Stewart.

The Spades would soon refine their lineup and change their name to The Mar-Keys, recording the 1961 Satellite single “Last Night,” featuring pianist Smoochy Smith. The song’s status as a bona fide regional hit made The Mar-Keys a sought-after live act in the southeast. But Cropper quickly returned home to Memphis, focusing his efforts on life in the studio. There, he’d ascend to the label’s A&R and frequent studio engineer, replacing Wayne “Chips” Moman, who’d split from the company before journeying to his own influential career in Southern rock, soul, and country.

With Cropper placed firmly at the forefront of operations in-studio, along with Satellite’s name change to Stax Records, the musician would aid in developing the powerhouse sound as a part of an enclave of session musicians who’d soon gel as the company’s house band. Beside Cropper, pianist and organist Booker T. Jones, drummer Al Jackson, Jr., and bassist Lewie Steinberg (who’d soon be replaced by Duck Dunn) would record instrumental “Green Onions,” hitting #3 on the R&B charts as Booker T. & The M.G.’s in 1962. Success as a performing act and session group would center the musicians as the baseline for the signature soul of Stax’s early period, all while Cropper co-wrote various compositions released by the label’s evolving stable of talent, including William Bell, Rufus and Carla Thomas, and Eddie Floyd.

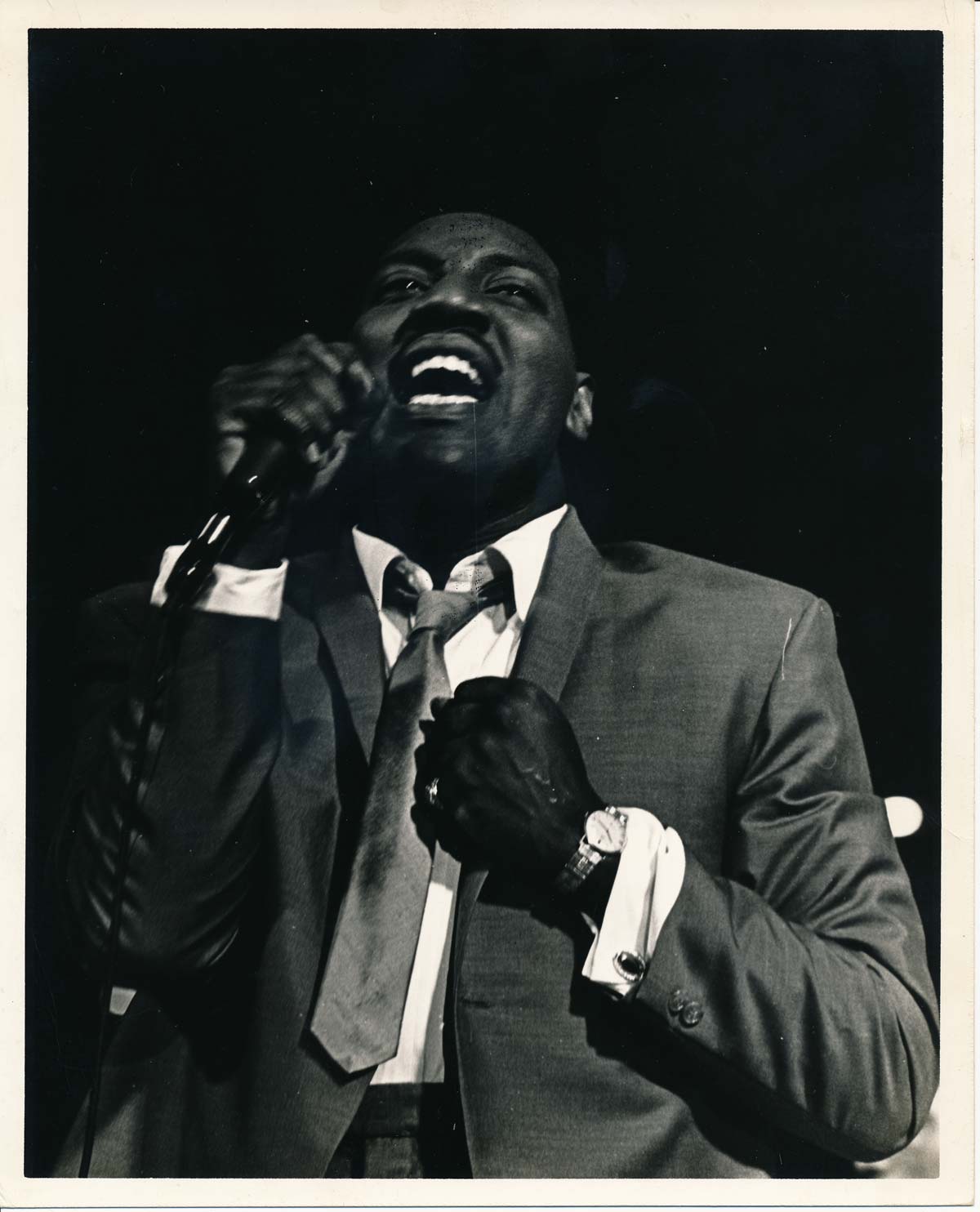

Otis Redding – photo courtesy of the Otis Redding Foundation

However, it was the unsuspected voice of a roadie traveling in support of a group of Georgia-based musicians that would serve as a spark to send Cropper and Stax into the stratosphere, taking the rest of Stax Records along for a historic ride.

Otis Redding, Jr., was born the son of a preacher on September 9, 1941, in Dawson, Georgia. His father, who also worked at the local Air Force Base, would move the family to Macon during Redding’s formative years. In his father’s church, he’d play drums and sing, while also learning the rudimentary elements of piano and guitar. Although he cut his teeth in the church, he’d quickly follow a fascination with rock and roll music, entering local talent shows and sneaking into nightclubs with a spot-on Little Richard impression. After dropping out of high school to enter the workforce. Redding would find a way to mold his Little Richard tribute into a traveling act, netting viable funds.

During a brief period of living with his sister in Los Angeles, Redding got one of his first chances to record, releasing the 1960 single “She’s All Right” backed with “Tuff Enuff” on Trans World Records, credited as The Shooters featuring Otis. The record would fail to find an audience.

Upon his return to Macon, Redding would begin traveling with live-wire guitarist Johnny Jenkins, who’d quickly find success on Atlantic Records with a pair of songs in 1962 called “Love Twist” and “Pinetop.” When Atlantic suggested Jenkins record his follow-up single at Stax in Memphis, Redding accompanied the showman, helping to load his equipment into the studio. The session wouldn’t prove fruitful for Jenkins, who was unable to lay down an inspired take. But the large roadie who assisted him with his gear was able to impress upon Cropper that he’d be worth giving a try on the mic with the remaining hours booked for the session.

Returning to his rock and roll roots, Redding recorded “Hey, Hey, Baby,” but it wasn’t until he tried his hand at “These Arms of Mine” that the remaining musicians in the studio woke up to the potential of Redding’s earth-shaking vocal talent. After the release of both songs as a single on sister label Volt, Jim Stewart invited Redding back eight months later in June 1963 to record “That’s What My Heart Needs” and ”Mary Little Lamb,” steadily growing Redding’s profile on the label.

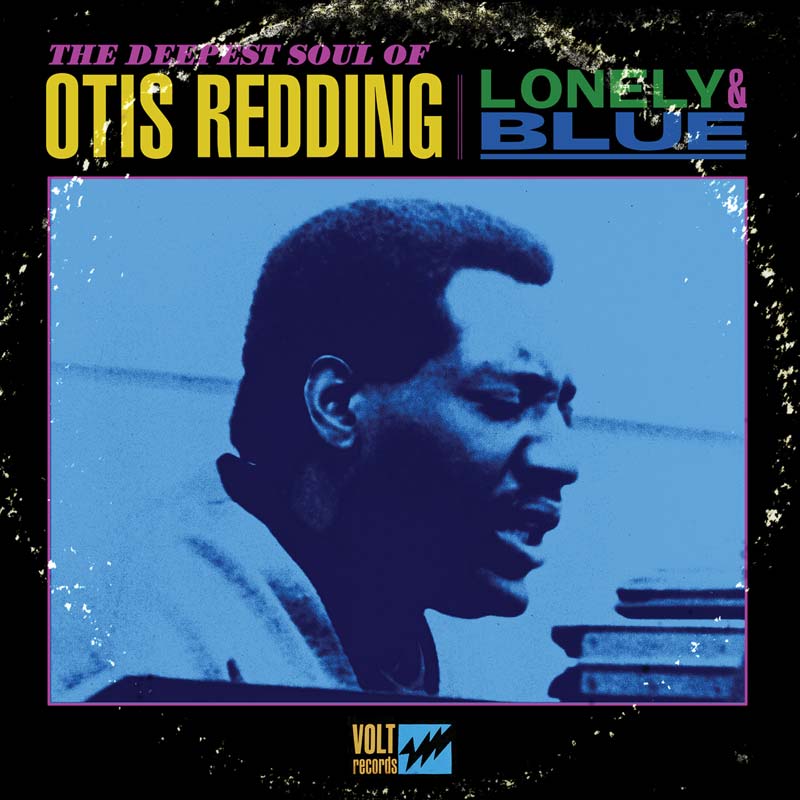

It wouldn’t be until 1964’s “Mr. Pitiful” that Cropper and Redding would connect as co-writers. The song borrows its premise from WDIA deejay A.C. “Moolah” Williams’ nickname for Redding, who he purported sounded pitiful and sad as an increasingly popular balladeer. At Cropper’s behest, Redding would lean into the persona with the tune, proving successful. “Mr. Pitiful” charted at #10 on R&B and #41 on pop charts.

Leaving pity aside, Redding’s meteoric rise within the company would include frequent chart-topping success and a star-turn as a trailblazing act on the road, domestically and abroad. He and Cropper would find success with two separate singles that dealt with emotion in a direct manner, “Fa-Fa-Fa-Fa (Sad Song)” and “The Happy Song (Dum, Dum),” with both offering standout showings on the U.S. charts.

Leaving pity aside, Redding’s meteoric rise within the company would include frequent chart-topping success and a star-turn as a trailblazing act on the road, domestically and abroad. He and Cropper would find success with two separate singles that dealt with emotion in a direct manner, “Fa-Fa-Fa-Fa (Sad Song)” and “The Happy Song (Dum, Dum),” with both offering standout showings on the U.S. charts.

Following success on the road with a monumental showing at Monterey International Pop Festival in the summer of 1967, Redding spent several days in a house boat recuperating near a pier in Sausalito, California. It was there that he’d develop an idea for a song inspired by life on the water.

On an unlikely break from performing and recording to have surgery to remove a polyp on his larynx, a rejuvenated Redding would return to Stax’s studio in November of that year with what he felt was a surefire hit, “(Sittin’ on the) Dock of the Bay.”

Though largely autobiographical, many of the elements that follow the plot of Redding’s life were implemented with Cropper’s input. Aside from Cropper and Redding’s insistence that the song would continue Redding’s reign as a chart-topping artist, Jim Stewart led a group of dissenting members of Stax’s core who felt the song was too stark in contrast, when compared to Redding’s recent output.

Unfortunately, Redding wouldn’t live to see the song’s completion, as he died in a plane crash in December 1967, along with all of the members of his recently-hired backing band The Bar-Kays, except for trumpeter Ben Cauley (who managed to survive the accident) and James Alexander (the lone member unable to secure a seat on the private charter).

Prompted by staffers to complete unheard Redding materials, Cropper returned to the composition, enhancing its iconic whistle-led outro and adding the natural sounds of seagulls and crashing waves to accompany Redding’s soul-shattering vocal performance.

Spending four weeks atop the U.S. Hot 100, the song was the first posthumous #1 hit in American music history, leading a feverish appetite in the marketplace for Redding’s music. The song netted Redding two Grammy ® Awards for Best R&B Performance and Best R&B Song in 1969.

The Songwriters Series ARCHIVE

Frederick Knight

Rance Allen

The Mad Lads

Carl Hampton and Homer Banks

Eddie Floyd and Al Bell

William Bell and Booker T. Jones

Eddie Marion, James Banks, and Henderson Thigpen

We Three (Bettye Crutcher, Raymond Jackson & Homer Banks)

Eddie Floyd and Steve Cropper

Booker T & the M.G.’s

Steve Cropper and Otis Redding