The Innovators: Stax Artist Spotlights

The Bar-Kays

At a convergent point between soul, funk, and rock ’n’ roll, The Bar-Kays boast what is arguably one of the most eclectic repertoires within the Stax Records family of performing acts. Off the stage, however, the group continues as perhaps the most enduring ensemble in all of music history, surviving the unthinkable to keep their legacy and name alive in rhythm.

At a convergent point between soul, funk, and rock ’n’ roll, The Bar-Kays boast what is arguably one of the most eclectic repertoires within the Stax Records family of performing acts. Off the stage, however, the group continues as perhaps the most enduring ensemble in all of music history, surviving the unthinkable to keep their legacy and name alive in rhythm.

The group came together in South Memphis, originally as The Imperials, with saxophonist Phalon Jones, drummer Carl Cunningham, guitarist Jimmy King, bassist James Alexander, and trumpeter Ben Cauley, who all attended Booker T. Washington High School. Quickly becoming a dominant fixture at school functions and talent shows, the young musicians would soon feature a head-turning addition to their band in the form of keyboard player Ronnie Caldwell. The white teenage musician not only integrated The Bar-Kays, a certainly uncommon occurrence for 1960s Memphis—his commitment to music even prompted him to change schools. Following his bandmates to Booker T. Washington, Caldwell pleaded with his reluctant parents to allow him to attend their primarily Black high school so that he could readily rehearse with his friends as soon as the bell rang for dismissal.

The precocious schoolmates developed a penchant for partying that helped them coin a new name. Inspired by the taste and popularity of Bacardi rum, they manufactured the moniker The Bar-Kays to demystify the adult beverage frequently snuck into their adolescent neighborhood parties and parking lot hang-outs.

After repeat visits to Stax Records in search of a recording contract, the group eventually garnered the enthusiasm of label founder Jim Stewart, who put The Bar-Kays to work on a debut album. In short order, Stewart identified the potential of a dance groove that would come to be known as “Soul Finger,” identifiable by its horn-laden opening fanfare. The single soared to No.3 on the Billboard R&B chart in spring 1967. Its B-side, “Knucklehead,” a nickname the band had given their bassist, crept into hit territory as well, peaking at No.28 on the R&B chart. Although the success of the single release hinted at a warm reception for the album, also titled Soul Finger, the LP failed to impact the market commercially, despite an express involvement by superstar labelmates Booker T. & the M.G.’s, whose leader offered liner notes to the junior ensemble’s debut effort.

Undeterred, the band made effective use of their emerging stardom at home. And, as the need for Stax to support its brightest solo star, Otis Redding, grew to be an outsized task, the group rose to the occasion. Impressed by The Bar-Kays’ onstage ability, following a night sitting in with the band at an impromptu performance in a local club, Redding offered the boys a gig—although the bandmates’ parents would intervene, imploring them to focus on school instead of a life on the road.

And so it would be. Almost before the boys’ graduation caps could fall to the ground, their robes were off, and The Bar-Kays were on their way to the Apollo Theater in Harlem to prove they were ready for the big time behind Otis Redding. Following their emphatic debut surrounding a slate of shows at the iconic New York City venue, the group, and the soul star fulfilled a dizzying tour schedule that would halt suddenly mere months later. Redding underwent surgery to remove polyps from his vocal cords, giving the band a much-deserved break.

The Bar-Kays

Determined to push forward, Cauley and Alexander chose to carry on The Bar-Kays’ name with a new group of musicians shortly after laying their childhood friends to rest. They cited an eternal vow the original band made together to endure if anything ever happened to one of them. Teaming with producer Allen Jones, the reformed lineup included guitarist Michael Toles, saxophonist Harvey Henderson, and drummers Willie Hall and Roy Cunningham (Carl’s younger brother). Interestingly, the group also recruited another white keyboardist, Ronnie Gorden, although it is uncertain whether it was by coincidence or for the sake of continuity.

Making their reintroduction to the world, The Bar-Kays showcased their new faces and sound on their sophomore LP, Gotta Groove, in 1969. Additionally, the group returned to its duties as a secondary house band for Stax’s stable of artists. And in this realm, they found immediate breakout success with the label’s unlikely new solo star, when staff writer Isaac Hayes stepped out front. His second album, Hot Buttered Soul, became a breakout hit for the label in the same year and is largely credited for saving the company in a desperate period going into the next decade.

Though Ronnie Gorden and Roy Cunningham would exit, shortly after the group began picking up steam again, Winston Stewart would join up to fill the gap on keys. Additionally, the previously instrumental outfit turned to vocalist Larry Dodson to add a new element to their performance. The change in direction aided the group in staying relevant during changing times, as soul fans developed a growing appetite for a new flavor called funk. Infusing elements of psychedelia and album-oriented rock, The Bar-Kays made an impassioned pivot that helped their third album, Black Rock, reach renewed chart success for the group. It made No.12 on the R&B albums chart and cracked the upper reaches of the Pop chart at No.90.

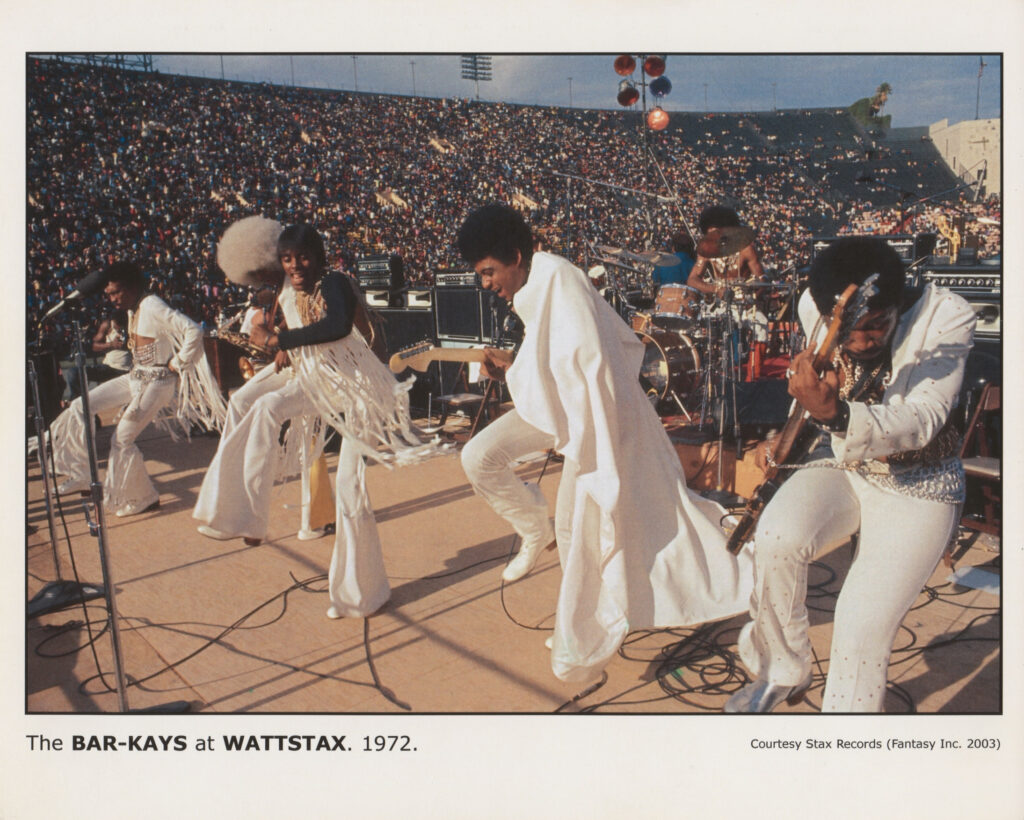

Growing in stature alongside Isaac Hayes, The Bar-Kays benefitted from another of his marquee successes, “Theme from Shaft,” from which they derived their “Son of Shaft.” At Stax’s 1972 music festival, which would come to be known as Wattstax, when it was released in theaters the following year, The Bar-Kays performed the song. As a single, it earned the band a No.10 hit on the R&B chart and a No.53 spot on the Pop chart.

Also in 1972, the group had moderate success with their album Do You See What I See?, their last to break through the chart while a part of the Stax-Volt family. They’d see one more album as active members of the label, Cold Blooded, in 1974, though it failed to land with consumers in the wake of Stax Records’ waning days of operation.

Resurfacing on Mercury Records and doubling down on their funkier sensibilities, The Bar-Kays found new footing. However, their next signature hit came from an unlikely source. Despite being signed to a new label for two years, a previously unreleased Bar-Kays track, “Holy Ghost,” was issued by Fantasy Records, which had just assumed control of the Stax Records brand and recordings.

With various lineups, albums, and accolades through the decades, The Bar-Kays remain a global entity identified by fans as a staple of funk purism and individualism with their freak-forward stage productions—best signified by lead singer Larry Dodson and his penchant for appearing with a snake draped around his neck. Keeping his vow to the original group, the last surviving member of the band’s first lineup still records and tours annually with a brand-new cast of musicians under the Bar-Kays banner.

The Innovators: Stax Artist Spotlights ARCHIVE

Stax Records — After 1975

Ollie & The Nightingales

The Bar-Kays

24-Carat Black

The Temprees

The Soul Children

The Mar-Keys

Delaney & Bonnie

Stax Groups – The Astors, Jeanne & The Darlings & the Charmels

The Mad Lads

The Dramatics

The Emotions

Johnnie Taylor

The Bar-Kays

Otis Redding

The Dramatics

RUFUS & CARLA THOMAS

Sam & Dave

The Emotions