The Innovators: Stax Artist Spotlights

The Soul Children

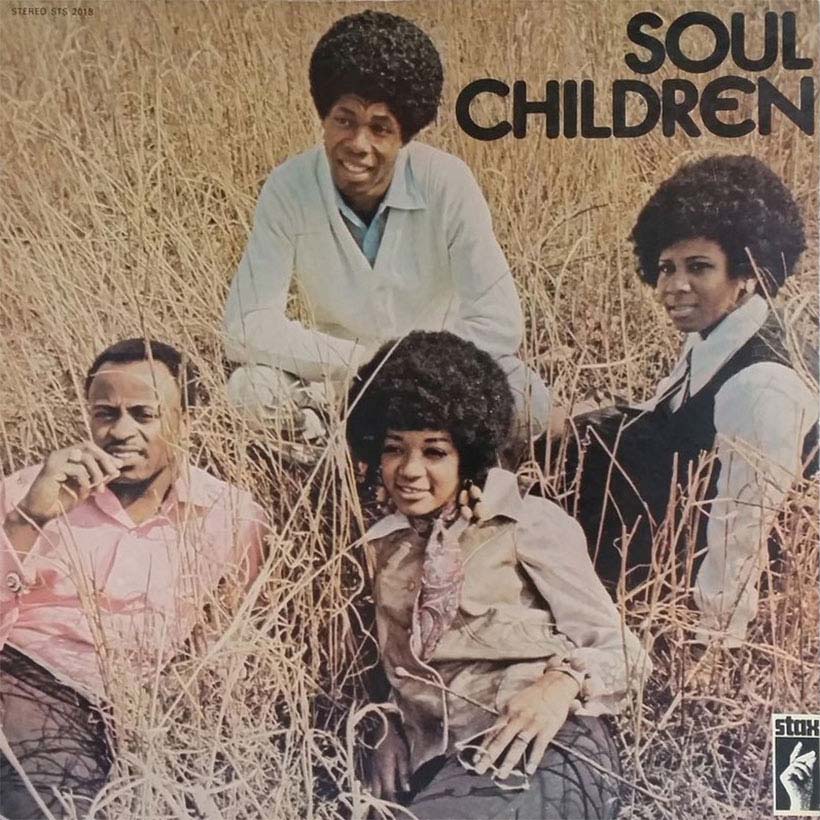

The Soul Children

Amid Stax Records’ “Soul Explosion,” a historic marketing push to re-establish its foothold in the soul music genre by introducing nearly 30 new LPs into the marketplace, The Soul Children debuted with an auspicious name. They were, indeed, a group manufactured to commemorate a new era of Stax, as the label’s staff and sound evolved into the 1970s.

As the primary hitmaking songwriters responsible for a string of ubiquitous hits in the 1960s, David Porter and Isaac Hayes entered a new decade devoid of access to Sam & Dave, the exciting duo that drove alongside them on their journey to chart-topping success. In the dissolution of Stax’s agreement with their former distributor Atlantic Records, Sam & Dave returned their talents to the parent company, which had effectively loaned their services to the emerging Southern hub of soul music.

Interested in cultivating a new star to perform their material, Hayes and Porter took an interest in John Colbert, a native of Greenville, Mississippi, known to audiences around the Mississippi Delta as J. Blackfoot. However, after early sessions left Hayes and Porter somewhat dissatisfied with what they were hearing, they considered how Blackfoot might sound with the accompaniment of a group. Soon, Blackfoot would be in sessions alongside Norman West (formerly of The Del-Rios, a group who’d previously recorded for Stax), Anita Louis, and Shelbra Bennett. Reworking songs originally intended for a J. Blackfoot solo effort, the co-ed ensemble debuted with “Give ’Em Love” and “I’ll Understand.” Both singles cracked the R&B singles chart in the fall of 1968. The following spring, The Soul Children found moderate success with “Tighten Up My Thang.” Beyond the group’s utilization of male and female vocals to compliment Blackfoot’s distinct rasp, each single displayed a markedly streetwise style of lyricism specific to the hip lingo of in-the-know Black youth.

Soul Children debut album

In May 1969, The Soul Children released their self-titled debut LP. Guided by its earlier singles, the album shot to the upper reaches of the Top R&B album chart, peaking comfortably at the No.9 position. As the album enjoyed its impressive outing as a commercial success, The Soul Children capitalized with their fourth and most successful single from the LP, “The Sweeter He is Part 1,” which found its way to No.7 on the R&B chart and No.52 on the pop chart. Fittingly, as a tribute to Hayes and Porter’s former collaborators, The Soul Children released their own version of Sam & Dave’s marquee hit “Hold on I’m Coming,” as a single of their own in 1970. By that time, Isaac Hayes’ position as one-half of the company’s most lucrative songwriting team had evolved into a more prominent role as one of the Stax Organization’s most treasured solo performers. As a result, his priorities began to shift, leaving little time for productivity as a shepherd over other acts’ careers.

In lieu of Hayes’ participation, Porter commenced conceiving a follow-up effort by The Soul Children with a new songwriting and production partner, Ronnie Williams. While the group’s debut garnered them relative breakout success their sophomore LP, Best of Two Worlds merely crept into relevancy in 1971, with the quartet unable to place any semblance of a hit on the singles charts. Despite a staple single to push the album into radio and jukeboxes, the album limped along to No.20 on the R&B album chart.

The group’s third LP, Genesis, released in 1972 found The Soul Children largely under the tutelage of Stax Records founder Jim Stewart alongside Booker T. & The M.G.’s drummer Al Jackson, Jr. as producers. With that duo at the helm of the project, the record boasts an all-star assortment of Stax songwriting talent, including selections from Bettye Crutcher, Homer Banks, Raymond Jackson, Carl Hampton, Eddie Floyd, John Gary Williams, and Tommy Tate. Even with all hands on deck, the album is punctuated by a single written by Soul Children group members J. Blackfoot and Norman West. The up-tempo number called “Hearsay,” found the group members entangled in a world of gossip centering around suspicious lovers accusing one another of infidelity. The single invigorated The Soul Children, charting at No.5 on the R&B singles chart and returning to a respectable No.44 on the Pop Chart. Coincidentally, The Soul Children would continue a successful streak of singles directly following “Hearsay,” albeit none of their releases immediately after found a home on an album. Specifically, the powerhouse single “Don’t Take My Kindness for Weakness,” written by Henderson Thigpen, James Banks, and Eddie Marion, made its way to the public during this in-between period, becoming a signature track for the group, reaching No.14 on the R&B chart.

The Soul Children’s career on Stax Records came to an end with one of their highest highs, a single charging at No.3 on the R&B chart called “I’ll Be the Other Woman,” which carried their final Stax album, “Friction,” to a decent showing on the album chart in 1974.

With Stax Records closing operations in 1975, The Soul Children moved their talents to Epic Records, within the CBS company. But that wouldn’t be the only change. The group began their new era as a trio, with Shelbra Bennett deciding to pursue a solo career. After two LPs with the label only produced a ripple of their former success with the Stax Record Company, the group got a second chance under the Stax banner. In 1978, they released “Open Door Policy” through a short-lived revamped version of Stax Records, relaunched by Fantasy Records. The album re-established their connection to David Porter, who’d reemerged to collaborate with the group during their time on Epic.

The group dissolved after the album was released, but vocalist J. Blackfoot ascended as a champion of the Southern Soul circuit. Working primarily with Homer Banks as a producer and frequent songwriter, Blackfoot, once again, became a staple as a solo artist on-stage and in-studio. Alone, he released his defining single, the solemn and soulful “Taxi,” in 1983. The song and its accompanying album City Slicker, propelled Blackfoot into regional stardom until his passing in 2011.

by Jared Boyd

The Innovators: Stax Artist Spotlights ARCHIVE

Stax Records — After 1975

Ollie & The Nightingales

The Bar-Kays

24-Carat Black

The Temprees

The Soul Children

The Mar-Keys

Delaney & Bonnie

Stax Groups – The Astors, Jeanne & The Darlings & the Charmels

The Mad Lads

The Dramatics

The Emotions

Johnnie Taylor

The Bar-Kays

Otis Redding

The Dramatics

RUFUS & CARLA THOMAS

Sam & Dave

The Emotions